Agent Orange

Agent Orange is the code name for one of the herbicides and defoliants used by the U.S. military in its herbicidal warfare program during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1971.

It was by far the most widely used of the so-called "Rainbow Herbicides". During the Vietnam war, between 1962 and 1971, the United States military sprayed 20,000,000 US gallons (80,000,000 L) of chemical herbicides and defoliants in Vietnam, eastern Laos and parts of Cambodia, as part of the aerial defoliation program known as Operation Ranch Hand.[1] The goal was to defoliate rural/forested land, depriving guerrillas of food and cover. The program was also a part of a general policy of forced draft urbanization, which aimed to destroy the ability of peasants to support themselves in the countryside, forcing them to flee to the U.S. dominated cities, depriving the guerrillas of their rural support base.[2][3]

Air Force records show that at least 6,542 spraying missions took place over the course of Operation Ranch Hand.[4] By 1971, 12 percent of the total area of South Vietnam had been sprayed with defoliating chemicals, which were often applied at rates that were 13 times as high as the legal USDA limit.[5] In South Vietnam alone, an estimated 10 million hectares of agricultural land were ultimately destroyed.[6] In some areas TCDD concentrations in soil and water were hundreds of times greater than the levels considered "safe" by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.[7][8]

By 1971, 12 percent of the total area of South Vietnam had been sprayed with defoliating chemicals, which were often applied at rates that were 13 times as high as the legal USDA limit.[5] In South Vietnam alone, an estimated 10 million hectares of agricultural land were ultimately destroyed.[6] Overall, more than 20% of South Vietnam's forests were sprayed at least once over a nine year period.[3]

The US began to target food crops in October 1962, primarily using Agent Blue. In 1965, 42 percent of all herbicide spraying was dedicated to food crops.[3] Rural-to-urban migration rates dramatically increased in South Vietnam, as peasants escaped the destruction and famine in the countryside by fleeing to the U.S.-dominated cities. The urban population in South Vietnam more than tripled: from 2.8 million people in 1958, to 8 million by 1971. The rapid flow of people led to a fast-paced and uncontrolled urbanization; an estimated 1.5 million people were living in Saigon slums, while many South Vietnamese elites and U.S. personnel lived in luxury.[9]

According to Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 4.8 million Vietnamese people were exposed to Agent Orange, resulting in 400,000 people being killed or maimed, and 500,000 children born with birth defects.[10]

Contents

|

Early development

The earliest form of the compound triiodobenzoic acid was studied by Arthur Galston as a plant growth hormone. The research was motivated by the desire to adapt soybeans for short growing season. Arthur Galston is widely known for the social impact his work had on science. This defoliant was modeled after Galston’s discovery of triiodobenzoic acid in 1943. Galston was especially concerned about the compound’s side effects to humans and the environment.[11]

Galston found that excessive usage of the compound caused catastrophic defoliation — a finding used by his colleague Ian Sussex to develop a family of herbicides[12] (Galston later campaigned against its use in Vietnam). These herbicides were developed during the 1940s by independent teams in England and the United States for use in controlling broad-leaf plants.

Phenoxyl agents work by mimicking a plant growth hormone, indoleacetic acid (IAA). When sprayed on broad-leaf plants they induce rapid, uncontrolled growth, eventually defoliating them. When sprayed on crops such as wheat or corn, it selectively kills only the broad-leaf weeds in the field, leaving the crop relatively unaffected. First introduced in 1946 in the agricultural farms of Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, these herbicides were in widespread use in agriculture by the middle of the 1950s.

The US government began to explore the use of tactical herbicides in warfare in the mid 1940s. During the 1950s they began to focus on delivery systems of spray tanks and nozzles. The first large scale test using 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T against foliage to improve visibility took place in June 1959 in Fort Drum, NY (Camp Drum). Testing of various herbicides and spray systems continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s in Puerto Rico and the US. The first test run of herbicides (Agent Purple) in Vietnam took place on August 10, 1961. Agent Orange became the herbicide of choice for defoliation of forests in Vietnam and Laos in 1965 until the health concerns of 2,4,5-T ended its use by the US military in April 1970.

Chemical description and toxicology

Agent Orange was given its name from the color of the orange-striped 55 US gallons (210 L) barrels in which it was shipped.[13]

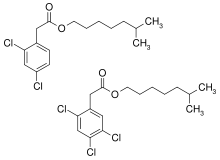

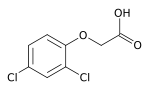

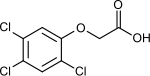

Chemically, it is a roughly 1:1 mixture of two phenoxyl herbicides in iso-octyl ester form, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T).

Numerous studies have examined health effects linked to Agent Orange, its component compounds, and its manufacturing byproducts.[14] Prior to the controversy surrounding Agent Orange, there was already a large body of scientific evidence linking 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D to serious negative health effects and ecological damage.[15]

It was revealed to the public in 1969 that the 2,4,5-T was contaminated with a dioxin, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (TCDD); and it was the TCDD that was causing these adverse health effects.[16] Internal memos from the companies that manufactured 2,4,5-T reveal that they had known as early as 1965 that Agent Orange was sold to the U.S. government for use in Vietnam that 2,4,5-T was contaminated with TCDD.[17]

TCDD has been comprehensively studied. It has been associated with increased neoplasms in every animal bioassay reported in the scientific literature.[18] The National Toxicology Program has classified TCDD as known to be a human carcinogen, frequently associated with soft-tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).[19][20]

Starting in 1991 the US Congress tasked the Institute of Medicine to review the scientific literature on Agent Orange and the other herbicides used in Vietnam, including their active ingredients and the dioxin contaminant. The IOM found an association found between dioxin exposure and diabetes.[21][22]

Three studies have suggested that prior exposure to Agent Orange poses an increase in the risk of acute myelogenous leukemia in the children of Vietnam veterans.[14]

While the two herbicides that make up Agent Orange 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T remain toxic over a short period—a scale of days or weeks—they quickly degrade. However, a 1969 report authored by K. Diane Courtney and others found that 2,4,5-T could cause birth defects and still births in mice.[23] Several studies have shown an increase rate of cancer mortality for workers exposed to 2,4,5-T. In one such study, from Hamburg, Germany, the risk of cancer mortality increased by 170% after working for 10 years at the 2,4,5-T producing section of a Hamburg manufacturing plant.[18]

Use in the Vietnam War

During the Vietnam war, between 1962 and 1971, the United States military sprayed 20,000,000 US gallons (80,000,000 L) of chemical herbicides and defoliants in Vietnam, eastern Laos and parts of Cambodia, as part of the aerial defoliation program known as Operation Ranch Hand.[1] The goal was to defoliate rural/forested land, depriving guerrillas of food and cover and clearing in sensitive areas such as around base perimeters.[24] The program was also a part of a general policy of forced draft urbanization, which aimed to destroy the ability of peasants to support themselves in the countryside, forcing them to flee to the U.S. dominated cities, depriving the guerrillas of their rural support base.[2][3]

The first batch of herbicides was unloaded at Tan Son Nhut Airbase in South Vietnam, on January 9, 1962.[13] Air Force records show that at least 6,542 spraying missions took place over the course of Operation Ranch Hand.[4] By 1971, 12 percent of the total area of South Vietnam had been sprayed with defoliating chemicals, which were often applied at rates that were 13 times as high as the legal USDA limit.[5] In South Vietnam alone, an estimated 10 million hectares of agricultural land were ultimately destroyed.[6] In some areas TCDD concentrations in soil and water were hundreds of times greater than the levels considered "safe" by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.[7][8]

The campaign destroyed 5 million acres (20,000 km2) of upland and mangrove forests and about 500,000 acres (2,000 km2) of crops. Overall, more than 20% of South Vietnam's forests were sprayed at least once over a nine year period.[3]

The US began to target food crops in October 1962, primarily using Agent Blue. In 1965, 42 percent of all herbicide spraying was dedicated to food crops.[3]

Effects on the Vietnamese people

According to Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 4.8 million Vietnamese people were exposed to Agent Orange, resulting in 400,000 deaths and disabilities, and 500,000 children born with birth defects.[10]

According to Vietnam Red Cross as many as 3 million Vietnamese people have been affected by Agent Orange including at least 150,000 children born with birth defects. The issue of whether or not exposure to dioxin has affected the health of the Vietnamese has been debated since the time of the war when the first animal studies were released showing that TCDD causes cancer and birth defects in rodents. Vietnamese scientists have been conducting epidemiological research on the impact of dioxin to human health since the late 1960s.[25]

Rural-to-urban migration rates dramatically increased in South Vietnam, as peasants escaped the destruction in the countryside by fleeing to the U.S.-dominated cities. The urban population in South Vietnam more than tripled: from 2.8 million people in 1958, to 8 million by 1971. The rapid flow of people led to a fast-paced and uncontrolled urbanization; an estimated 1.5 million people were living in Saigon slums, while many South Vietnamese elites and U.S. personnel lived in luxury.[9]

The question of dioxin’s impact on reproductive health and birth outcomes is even more controversial, in part because the research done in Vietnam has not for the most part been peer reviewed or published in scientific journals. Whereas the US Institute of Medicine has found only spina bifida and anencephaly to be associated with paternal exposure to dioxin the Vietnamese researchers have found in studies of both exposed males and females that there is an increased risk of abnormal birth outcomes including infertility, miscarriages, still births, and birth defects compared to those who were not exposed. Among the birth defects, spina bifida, hydrocephaly, malformations of the extremities, musculature issues, developmental disabilities, congenital heart defects and cleft-palate are found. There are also higher rates of children with multiple disabilities among exposed populations. These are many of the same birth defects that the US Veterans Administration allows for compensation for female veterans, though it is due to these birth defects being associated with service in Vietnam and not directly to Agent Orange/dioxin.

The most affected zones are the mountainous area along Truong Son (Long Mountains) and the border between Vietnam and Cambodia. The affected residents are living in sub-standard conditions with many genetic diseases.[26]

Dioxin hotspots

For more than a decade The Hatfield Group from Vancouver, Canada has been researching the long-term environmental effects of Agent Orange. Their extensive research has found that the areas sprayed by Agent Orange during the war no longer contain measurable amounts of dioxin and do not pose a health threat.[27] About 28 of the former US military bases in Vietnam where the herbicides were stored and loaded onto airplanes still have high level of dioxins in the soil posing a health threat to the surrounding communities.

These 'hotspots' have dioxin contamination that is up to 350 times higher than international recommendations for action. The contaminated soil and sediment continue to affect the citizens of Vietnam, poisoning their food chain and causing illnesses, serious skin diseases as well as a variety of cancers in the lungs, larynx, and prostate.[28] The airbases in Bien Hoa, Da Nang and Phu Cat have been put on a priority list for clean-up or containment by the Vietnamese government.[29]

Children in the areas where Agent Orange was used have been affected and have multiple health problems including cleft palate, mental disabilities, hernias, and extra fingers and toes.[28]

Effects on U.S. veterans

Studies of veterans who served in the south during the war compared to those who did not have found that those who went south have increased rates of cancer, nerve, digestive, skin and respiratory disorders. Among the cancers veterans from the south had higher rates of throat cancer, acute/chronic leukemia, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, prostate cancer, lung cancer, soft tissue sarcoma and liver cancer. Other than liver cancer, these are the same conditions that the US Veteran’s Administration has found to be associated with exposure to Agent Orange/dioxin and are on the list of conditions eligible for compensation and treatment.[25]

While in Vietnam, the veterans were told not to worry, and were persuaded that the chemical was harmless.[30] However, after returning home, Vietnam Veterans began to suspect that their ill health or the instances of their wives having miscarriages or children born with birth defects may be related to Agent Orange and the other toxic herbicides they were exposed to in Vietnam. Veterans began to file claims in 1977 to the Department of Veterans Affairs for disability payments or health care for conditions that they believed were associated with exposure Agent Orange, or more specifically dioxin, but their claims were denied unless they could prove that the condition began when they were in the service or within one year of their discharge.

In a November 2004 Zogby International poll of 987 people, 79% of respondents thought that the US chemical companies which produced Agent Orange defoliant should compensate US soldiers who were affected by the toxic chemical used during the war in Viet Nam. However, only 51% said they supported compensation for Vietnamese Agent Orange victims.[31]

By April 1993, only the Department of Veterans Affairs had only compensated 486 victims, although it had received disability claims from 39,419 soldiers who had been exposed to Agent Orange while serving in Vietnam.[32]

Legal and diplomatic proceedings

New Jersey Agent Orange Commission

In 1980, New Jersey created the New Jersey Agent Orange Commission, the first state commission created to study its effects. The commission's research project in association with Rutgers University was called "The Pointman Project". It was disbanded by Governor Christine Todd Whitman in 1996.[33]

During Pointman I, commission researchers devised ways to determine small dioxin levels in blood. Prior to this, such levels could only be found in the adipose (fat) tissue. The project compared dioxin levels in a small group of Vietnam veterans who had been exposed to Agent Orange with a group of matched veterans who had not served in Vietnam. The results of this project were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1988.[34]

The second phase of the project continued to examine and compare dioxin levels in various groups of Vietnam veterans including Army, Marines and brown water riverboat Navy personnel.

US Congress

In 1991, the US Congress enacted the Agent Orange Act giving the Department of Veterans Affairs the authority to declare certain conditions 'presumptive' to exposure to Agent Orange/Dioxin enabling these veterans who served in Vietnam eligible to receive treatment and compensation for these conditions.[35] The same law required the National Academy of Sciences to periodically review the science on dioxin and herbicides used in Vietnam to inform the Secretary of Veterans Affairs about the strength of the scientific evidence showing association between exposure to Agent Orange/Dioxin and certain conditions.[36]

Through this process, the list of 'presumptive' conditions has grown since 1991 and currently the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has listed prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, type II diabetes, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, peripheral neuropathy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and spina bifida in children of veterans exposed to Agent Orange as conditions associated with exposure to the herbicide. This list now includes B cell leukemias, such as hairy cell leukemia, Parkinson’s disease and ischemic heart disease, these last three having been added on August 31, 2010. There is currently a concern being voiced by several highly placed individuals in government about whether some of the diseases on the list should, in fact, actually have been included.[37]

US veterans class action lawsuit against manufacturers

Since at least 1978, several lawsuits have been filed against the companies which produced Agent Orange, among them Dow Chemical, Monsanto, and Diamond Alkali/Shamrock (which produced 5%[38]).

Hy Mayerson of the law firm The Mayerson Law Offices, P.C. was an early pioneer in Agent Orange litigation, working with renown environmental attorney Victor Yannacone in 1980 on the first class-action suits against wartime manufacturers of Agent Orange. In meeting Dr. Ronald A. Codario, one of the first civilian doctors to see afflicted patients, Mayerson, so impressed by the fact that an M.D. would show so much interest in a Vietnam veteran, forwarded more than a thousand pages of information on Agent Orange and the effects of dioxin on animals and humans to Codario's office the day after he was first contacted by the doctor.[39]

The Mayerson Law Offices, P.C., with Sgt. Charles E. Hartz as their principal client, filed the first Agent Orange class action lawsuit, in Pennsylvania in 1980, for the injuries that soldiers in Vietnam suffered through exposure to toxic dioxins in the Agent Orange defoliant.[40] Attorney Hy Mayerson co-wrote the brief that certified the Agent Orange Product Liability action as a class action, the largest ever filed as of its filing.[41] Hartz’s deposition was one of the first ever taken in America, and the first for an Agent Orange trial, for the purpose of preserving testimony at trial, as it was understood that Hartz would not live to see the trial because of the brain tumor that began to develop while he was a member of Tiger Force, Special Forces, and LRRPs in Vietnam.[42][43][44] The firm also located and supplied critical research to the Veterans’ lead expert Dr. Ronald A. Codario, M.D., including approximately one hundred articles from toxicology journals dating back more than a decade, as well as data about where herbicides had been sprayed, what the effects of dioxin had been on animals and humans, and every accident in factories where herbicides were produced or dioxin was a contaminant of some chemical reaction.[39]

U.S. veterans obtained a $180 million settlement in a class action lawsuit in 1984,[45] with most affected veterans receiving a one-time lump sum payment of $1,200. In Australia, Canada and New Zealand, veterans who were part of the lawsuit obtained compensation in the settlements that same year.

U.S./Vietnamese government negotiations

In 2002, Vietnam and the US held a joint conference on Human Health and Environmental Impacts of Agent Orange. Following the conference the US National Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences (NIEHS) began scientific exchanges between the US and Vietnam and began discussions for a joint research project on the human health impacts of Agent Orange.

These negotiations broke down in 2005 when neither side could agree on the research protocol and the research project was canceled. However, more progress has been made on the environmental front. In 2003 the first US-Vietnam workshop on remediation of dioxin was held.

Starting in 2005 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began to work with the Vietnamese government to measure the level of dioxin at the Da Nang Airbase. Also in 2005 the Joint Advisory Committee on Agent Orange made up of representatives of Vietnamese and US government agencies was established. The committee has been meeting yearly to explore areas of scientific cooperation, technical assistance and environmental remediation of dioxin.

A breakthrough in the diplomatic stalemate on this issue occurred as a result of United States President George W. Bush's state visit to Vietnam in November 2006. In the joint statement, President Bush and President Triet agreed that "further joint efforts to address the environmental contamination near former dioxin storage sites would make a valuable contribution to the continued development of their bilateral relationship.[46]

In late May 2007, President Bush signed into law a supplemental spending bill for the war in Iraq and Afghanistan that included an earmark of $3 million specifically for funding for programs for the remediation of dioxin 'hotspots' on former US military bases and for public health programs for the surrounding communities,[47] however some authors consider this to be completely inadequate, pointing out that the U.S. airbase in Danang, alone, will cost $14 million to clean up, and that three others are estimated to require $60 million for cleanup.[8] The appropriation was renewed in the fiscal year 2009 and again in FY 2010.

Vietnamese victims class action lawsuit in U.S. courts

On January 31, 2004, a victim's rights group, the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (VAVA), filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn, against several U.S. companies for liability in causing personal injury, by developing and producing the chemical. Dow Chemical and Monsanto were the two largest producers of Agent Orange for the U.S. military and were named in the suit along with the dozens of other companies (Diamond Shamrock, Uniroyal, Thompson Chemicals, Hercules, etc.). On March 10, 2005, Judge Jack B. Weinstein of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York - who had presided over the 1984 US veterans class action lawsuit - dismissed the lawsuit ruling that there was no legal basis for the plaintiffs' claims. He concluded that Agent Orange was not considered a poison under international law at the time of its use by the U.S.; that the U.S. was not prohibited from using it as a herbicide; and that the companies which produced the substance were not liable for the method of its use by the government. The U.S. government was not a party in the lawsuit, due to sovereign immunity, and the court ruled that the chemical companies, as contractors of the US government, shared the same immunity. The case was appealed and heard by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals on June 18, 2007. The Court of Appeals upheld the dismissal of the case stating that the herbicides used during the war were not intended to be used to poison humans and therefore did not violate international law.[48] The US Supreme Court declined to consider the case.

Three judges on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan heard the Appeals case on June 18, 2007. They upheld Weinstein's ruling to dismiss the case. They ruled that though the herbicides contained a dioxin (a known poison) they were not intended to be used as a poison on humans. Therefore they were not considered a chemical weapon and thus not a violation of international law. A further review of the case by the whole panel of judges of the Court of Appeals also confirmed this decision. The lawyers for the Vietnamese filed a petition to the US Supreme Court to hear the case. On March 2, 2009, the Supreme Court denied certiorari and refused to reconsider the ruling of the Court of Appeals.[49]

Help for those affected in Vietnam

In order to assist those who have been impacted by Agent Orange/Dioxin, the Vietnamese have established "Peace villages", which each host between 50 to 100 victims, giving them medical and psychological help. As of 2006, there were 11 such villages, thus granting some social protection to fewer than a thousand victims. U.S. veterans of the war in Vietnam and individuals who are aware and sympathetic to the impacts of Agent Orange have also supported these programs in Vietnam. An international group of Veterans from the U.S. and its allies during the Vietnam war working together with their former enemy — veterans from the Vietnam Veterans Association — established the Vietnam Friendship Village[50] located outside of Hanoi.

The center provides medical care, rehabilitation and vocational training for children and veterans from Vietnam who have been impacted by Agent Orange. In 1998, The Vietnam Red Cross established the Vietnam Agent Orange Victims Fund to provide direct assistance to families throughout Vietnam that have been impacted by Agent Orange. In 2003, the Vietnam Association of Victims of Agent Orange (VAVA) was formed. In addition to filing the lawsuit against the chemical companies, VAVA also provides medical care, rehabilitation services and financial assistance to those impacted by Agent Orange.

The Vietnamese government provides small monthly stipends to more than 200,000 Vietnamese believed affected by the herbicides; this totaled $40.8 million in 2008 alone. The Vietnam Red Cross has raised more than $22 million to assist the ill or disabled, and several U.S. foundations, United Nations agencies, European governments and non-governmental organizations have given a total of about $23 million for site cleanup, reforestation, and health care and other services to those in need.[51]

Use outside of Vietnam

While 'Agent Orange' was only used between 1965 and 1970, 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T and other herbicides were used by the US Military from the late 1940s through the 1970s.[52][53]

United States

A December 2006 Department of Defense report listed Agent Orange testing, storage, and disposal sites at 32 locations throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, Thailand, Puerto Rico, Korea, and in the Pacific Ocean.[54] The Veteran Administration has also acknowledged that Agent Orange was used domestically by U.S. forces in test sites throughout the US. Eglin Air Force Base in Florida was one of the primary testing sites throughout the 1960s.[55]

Korea

Agent Orange was used in Korea in the late 1960s.[56] Republic of Korea troops were the only personnel involved in the spraying, which occurred along the demilitarized zone with North Korea. "Citing declassified U.S. Department of Defense documents, Korean officials fear thousands of its soldiers may have come into contact with the deadly defoliant in the late 1960s and early 1970s. According to one top government official, as many as '30,000 Korean veterans are suffering from illness related to their exposure'. The exact number of GIs who may have been exposed is unknown. But C. David Benbow, a North Carolina attorney who served as a sergeant with Co. C, 3rd Bn., 23rd Inf. Regt., 2nd Div., along the DMZ in 1968-69, estimates as many as '4,000 soldiers at any given time' could have been affected.".[57]

In 1999, about 20,000 South Koreans filed two separated lawsuits against U.S. companies, seeking more than $5 billion in damages. After losing a decision in 2002, they filed an appeal.

In January 2006, the South Korean Appeals Court ordered Dow Chemical and Monsanto to pay $62 million in compensation to about 6,800 people. The ruling acknowledged that "the defendants failed to ensure safety as the defoliants manufactured by the defendants had higher levels of dioxins than standard", and, quoting the U.S. National Academy of Science report, declared that there was a "causal relationship" between Agent Orange and 11 diseases, including cancers of the lung, larynx and prostate. However, the judges failed to acknowledge "the relationship between the chemical and peripheral neuropathy, the disease most widespread among Agent Orange victims" according to the Mercury News.

Canadian Forces Base Gagetown (New Brunswick, Canada)

The U.S. military, with the permission of the Canadian government,[58] tested herbicides, including Agent Orange, in the forests near the Canadian Forces Base Gagetown in New Brunswick in 1966 and 1967. On September 12, 2007, Greg Thompson, Minister of Veterans Affairs, announced that the government of Canada was offering a one-time ex gratia payment of $20,000 as the compensation package for Agent Orange exposure at CFB Gagetown.[59]

On July 12, 2005, Merchant Law Group LLP on behalf of over 1,100 Canadian veterans and civilians who were living in and around the CFB Gagetown filed a lawsuit to pursue class action litigation concerning Agent Orange and Agent Purple with the Federal Court of Canada.[60]

On August 4, 2009, the case was rejected by the court due to lack of evidence. The ruling was appealed.[61][62]

Queensland, Australia

In 2008 Australian researcher Jean Williams claimed that cancer rates in Queensland, Australia were 10 times higher than the state average due to secret testing of Agent Orange by the Australian military scientists during the Vietnam War. Williams, who had won the Order of Australia medal for her research on the effects of chemicals on U.S. war veterans, based her allegations on Australian government reports found in the Australian War Memorial museum archives. A former soldier, Ted Bosworth, backed up the claims, saying that he had been involved in the secret testing. However, the Queensland health department claimed that cancer rates in Innisfail were not higher than those in other parts of the state.[63]

Brazil

The Brazilian government used Agent Orange to defoliate a large section of the Amazon rainforest so that Alcoa could build the Tucuruí dam to power mining operations. Large areas of rainforest were destroyed, along with the homes and livelihoods of thousands of rural peasants and indigenous tribes.[64]

Malayan Emergency

Small scale defoliation experiments using 2-4-D and 2-4-5-T were conducted by the British during the Malayan Emergency in 1951. Areas of jungle close to roadways were cleared using chemical defoliation to help prevent ambushes by Communist Terrorists.[65]

See also

- Chemical warfare

- Depleted uranium

- Environmental issues with war

- Gulf War Syndrome

- Plan Colombia

- Operation Ranch Hand

- Teratogen

- Thalidomide

- Vietnam Syndrome

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pellow, David N. Resisting Global Toxics: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice, MIT Press, 2007, p. 159, (ISBN 0-262-16244-X).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Stellman et al. 2003: pp 681-687

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Kolko, Gabriel (1994). Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience. New Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 1-56584-218-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Furukawa, Hisao (2004). Ecological destruction, health, and development: advancing Asian paradigms. Trans Pacific Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781920901011. http://books.google.com/books?id=jPL4wSfgan4C&pg=PA143.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 SBSG, 1971: p. 36

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Luong, 2003: p. 3

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fawthrop, Tom; "Vietnam's war against Agent Orange", BBC News, June 14, 2004

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Fawthrop, Tom; "Agent of Suffering", Guardian, 10 February 2008

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Luong, 2003: pp. 4

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 York,Geoffrey; Mick, Hayley; "Last Ghost of the Vietnam War", The Globe and Mail, July 12, 2008

- ↑ Peterson, Doug Arthur W. Galston:Matters of Light, LASNews Magazine, University of Illinois, Spring 2005

- ↑ Pearce, Jeremy; Arthur Galston, Agent Orange Researcher, Is Dead at 88 - Obituary New York Times, June 23, 2008 (accessed=2008-08-18)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hay, 1982: p. 151

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Frumkin, 2003: pp.245-255

- ↑ Young, 2009: p. 2

- ↑ Young, 2009: p. 6

- ↑ Barlett, Donald P. and Steele, James B.; "Monsanto’s Harvest of Fear", Vanity Fair May 2008

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Dwyer and Flesch-Janys, "Editorial: Agent Orange in Vietnam", American Journal of Public Health, April 1995, Vol 85. No. 4, p. 476

- ↑ Committee Recommendations: 2,3,7,8- Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)

- ↑ NTP, 2006:

- ↑ "Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Type 2 Diabetes", Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, October 11, 2000

- ↑ "Data Suggest a Possible Association Between Agent Orange Exposure and Hypertension", Office of News and Public Information, National Academy of Sciences. Quote: "the report also concluded that there is suggestive but limited evidence that AL amyloidosis is associated with herbicide exposure"] (accessed:19 May 2008)

- ↑ Buckingham, 1992: Chapter IX - Ranch Hand Ends

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer. Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: Political, Social and Military History. ABC-CLIO, Inc. Santa Barbara. 1998.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Agent Orange: Diseases Associated with Agent Orange Exposure". Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards. 2010-03-25. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorange/diseases.asp. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs - [http://www.mofa.gov.vn/vi/tt_baochi/nr041126171753/ns050118101044 Support Agent Orange Victims in Vietnamese.

- ↑ Dwernychuk, Wayne et al. "The Agent Orange Dioxin Issue in Viet Nam: A Manageable Problem". Retrieved 2010-06016

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Agent Orange blights Vietnam". BBC News. December 3, 1998. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/227467.stm. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ↑ The Hatfield Consultants

- ↑ Hermann, Kenneth J.; "Killing Me Softly: How Agent Orange Murders Vietnam's Children", Political Affairs, April 25, 2006

- ↑ Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs; "Americans support compensations for Agent Orange victims: poll", November 22, 2004

- ↑ Fleischer, Doris Zames; Zames, Freida (2001). The disability rights movement: from charity to confrontation. Temple University Press. p. 178. ISBN 9781566398121. http://books.google.com/books?id=3t84d8tLEVcC&pg=PA178.

- ↑ New York Times, 3 July 1996

- ↑ Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 259 No. 11, 18 March 1988

- ↑ Agent Orange - Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards

- ↑ PL 102-4 and The National Academy of Sciences

- ↑ Baker, Mike (September 2, 2010). "Costs of aging vets concern deficit commission". The Air Force Times. http://www.airforcetimes.com/news/2010/08/ap-aging-vets-concern-083110/. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ↑ Answers.com - Ultramar Diamond Shamrock Corporation. Retrieved on 19 April 2007

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Wilcox, 1983:

- ↑ Dying Veteran May Speak From Beyond The Grave In Court: Lakeland Ledger

- ↑ Croft, Steve; Agent Orange, CBS Evening News, May 07, 1980

- ↑ "The Mayerson Law Offices". The Mayerson Law Offices. http://www.mayerson.com/html/about.html. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Earth: The Agent Orange Mystery: Omni Magazine

- ↑ Pottstown Mercury

- ↑ Stanley, Jay; Blair, John D., ed (1993). Challenges in military health care: perspectives on health status and the provision of care. Transaction Publishers. p. 164. ISBN 9781560006503. http://books.google.com/books?id=8k-WIJYwIF4C&pg=PA164.

- ↑ Joint Statement Between the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the United States of America. Pres. George W Bush Whitehouse Press office. Accessed 2008-12-31. (original no longer available PDF available at http://www.warlegacies.org/Bush.pdf.)

- ↑ Martin, May 2009:

- ↑ February 22, 2008 Decision by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals re: Vietnam Association of Victims of Agent Orange v. Dow Chemical Co.

- ↑ "Order List" (PDF). The United States Supreme Court. March 2, 2009. pp. 7. http://www.supremecourt.gov/orders/courtorders/030209zor.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ "Vietnam Friendship Village Project". http://www.vietnamfriendship.org. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ Statement by Amb. Ngo Quang Xuan to the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee of Asia, Pacific and Global Environment, June 2009, p. 3

- ↑ Agent Orange information site

- ↑ Specifics of Agent Orange use

- ↑ Young, 2006: pp. 5-6

- ↑ U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. "Report on DoD Herbicides Outside of Vietnam". http://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/agentorange/dod_herbicides_outside_vietnam.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. "Agent Orange: Information for Veterans Who Served in Vietnam". http://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/agentorange/AOIB10-49JUL03.pdf. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ "AGENT ORANGE UNITS SPRAYED OUTSIDE OF VIETNAM (KOREA)". http://cybersarges.tripod.com/aoinkorea.html. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ↑ "Quiet Complicity: Canadian Involvement in the Vietnam War, by Victor Levant (1986).". The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.canadianencyclopedia.ca/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0008367. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ↑ "People angry with Agent Orange package turn to class-action lawsuit". The Canadian Press. 2007-09-13. http://canadianpress.google.com/article/ALeqM5jf86SisH1AAn3uWIlyJPujHxvQhA. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ↑ "Agent Orange Class Action". Merchant Law Group LLP. http://www.merchantlaw.com/agentop.html. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ↑ Shawn Berry (August 4, 2009). "Moncton judge rules in Agent Orange lawsuit". The Times and Transcript. http://timestranscript.canadaeast.com/search/article/749829. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ timestranscript.com - Moncton judge rules in Agent Orange lawsuit | By SHAWN BERRY - Breaking News, New Brunswick, Canada

- ↑ McMahon, Barbara; "Australia cancer deaths linked to Agent Orange", Guardian, May 19, 2008

- ↑ Kevin Danaher, ed (1994). 50 Years is Enough. South End Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0896084957.

- ↑ "Psychological Warfare during the Malayan Emergency by Herbert A Friedman". http://www.psywar.org/malaya.php. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

Bibliography

- Buckingham, William (1992). Operation Ranch Hand: The Airforce and Herbicides in Southeast Asia 1961-1971. Office of Air Force History.

- Frumkin H (2003). "Agent Orange and cancer: an overview for clinicians". CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 53 (4): 245–55. doi:10.3322/canjclin.53.4.245. PMID 12924777. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12924777.

- Hay, Alastair (1982). The chemical scythe: lessons of 2, 4, 5-T, and dioxin. Springer. ISBN 9780306409738.

- Luong, Hy V. (2003). Postwar Vietnam: dynamics of a transforming society. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780847698653.

- Martin, Michael F.; Vietnamese Victims of Agent Orange and US-Vietnam Relations, Congressional Research Service, report to United States Congress, May 28, 2009

- Ngo, Anh D.; Taylor, Richard; Roberts, Christine L.; Nguyen, Tuan V. (March 16, 2006). "Association between Agent Orange and birth defects: systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Epidemiology. http://www.vn-agentorange.org/edmaterials/ije_paper.pdf.

- NTP (National Toxicology Program); "Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in Female Harlan Sprague-Dawley Rats (Gavage Studies)", CASRN 1746-01-6, April, 2006.

- SBSG (Stanford Biology Study Group) (May 1971). "The Destruction of Indochina". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 27 (5): 36–40. ISSN 0096-3402. http://books.google.com/books?id=agsAAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA36.

- Stellman et al., Jeanne (17 April 2003). "The Extent and patterns of usage of Agent Orange and other Herbicides in Vietnam". Nature 422: 681–687. http://www.vn-agentorange.org/edmaterials/nature01537.pdf.

- Wilcox, Fred (1983). Waiting for an Army to Die: The Tragedy of Agent Orange (1st ed.). Random House, Inc.. ISBN 9780932020680.

- Young, Alvin L. (December 2006). "The History of the US Department of Defense Programs for the Testing, Evaluation, and Storage of Tactical Herbicides". http://www.dod.mil/pubs/foi/reading_room/TacticalHerbicides.pdf. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- Young, Alvin L. (2009). The History, Use, Disposition and Environmental Fate of Agent Orange. Springer. ISBN 9780387874852. http://books.google.com/books?id=1iCHpk2fZksC.

Further reading

Books

- (in French) L'agent orange au Viet-nam: Crime d'hier, tragédie d'aujourd'hui. Tiresias editions. 2005. ISBN 2-91523-23-6.

- Cecil, Paul Frederick (1986). Herbicidal warfare: the Ranch Hand Project in Vietnam. Praeger. ISBN 9780275920074.

- Đại, Lê Cao (2000). Agent Orange in the Vietnam War: History and Consequences. Vietnam Red Cross Society.

- Gibbs, Lois Marie (1995). "Agent Orange and Vietnam Veterans". Dying From Dioxins. South End Press. pp. 14–20. ISBN 9780896085251. http://books.google.com/books?id=MuMFYQ8CbEgC&pg=PA14.

- Griffiths, Philip Jones (2004). Agent Orange: Collateral Damage in Vietnam. Alpen Editions. ISBN 978-1904563051.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine, Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides) (1994). Veterans and Agent Orange: health effects of herbicides used in Vietnam. National Academies Press". ISBN 9780309048873. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2141.

- Linedecker, Clifford; Ryan, Michael; Ryan, Maureen (1982). Kerry: Agent Orange and an American Family (1st ed.). St. Martins Press. ISBN 978-0312451127.

- Nicosia, Gerald (2001). Home to War: A History of the Vietnam Veterans Movement. Crown. ISBN 978-0812991031.

- Schecter, Arnold (1994). Dioxins and health. Springer. ISBN 9780306447853.

- Schuck, Peter (1987). Agent Orange on trial: mass toxic disasters in the courts. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674010260.

- Uhl, Michael; Ensign, Tod (1980). GI Guinea Pigs: How the Pentagon Exposed Our Troops to Dangers Deadlier than War (1st ed.). Playboy Press. ISBN 978-0872235694.

Journal articles / Papers

- Weisman, Joan Murray. The Effects of Exposure to Agent Orange on the Intellectual Functioning, Academic Achievement, Visual Motor Skill, and Activity Level of the Offspring of Vietnam War Veterans. Doctoral thesis. Hofstra University. 1986.

- Kuehn, Bridget M.; Agent Orange Effects, Journal of the American Medical Association, 2010;303(8):722.

Government/NGO reports

- "Agent Orange in Vietnam: Recent Developments in Remediation: Testimony of Ms. Tran Thi Hoan", Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific and the Global Environment, U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs. July 15, 2010

- "Agent Orange in Vietnam: Recent Developments in Remediation: Testimony of Dr. Nguyen Thi Ngoc Phuong", Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific and the Global Environment, U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs. July 15, 2010

- Agent Orange Policy, American Public Health Association, 2007

- "Assessment of the health risk of dioxins", World Health Organization/International Programme on Chemical Safety, 1998

- Operation Ranch Hand: Herbicides In Southeast Asia History of Operation Ranch Hand, 1983

News

- Fawthrop, Tom; Agent of suffering, Guardian, 10 February 2008

- Cox, Paul; "The Legacy of Agent Orange is a Continuing Focus of VVAW", The Veteran, Vietnam Veterans Against the War, Volume 38, No. 2, Fall 2008.

- Quick, Ben "The Boneyard" Orion Magazine, March/April 2008

- Cheng, Eva; "Vietnam's Agent Orange victims call for solidarity", Green Left Weekly, September 28, 2005

- Children and the Vietnam War 30-40 years after the use of Agent Orange

Video

- Agent Orange: The Last Battle. Dir. Stephanie Jobe, Adam Scholl. DVD. 2005

External links

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency - Dioxin Web site

- Agent Orange Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards, U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs

- Poisoned Lives

|

|||||